Intron Loss and Molecular Evolution Rate of rpoC1 in Ferns

Received date: 2019-06-06

Accepted date: 2020-03-24

Online published: 2020-04-15

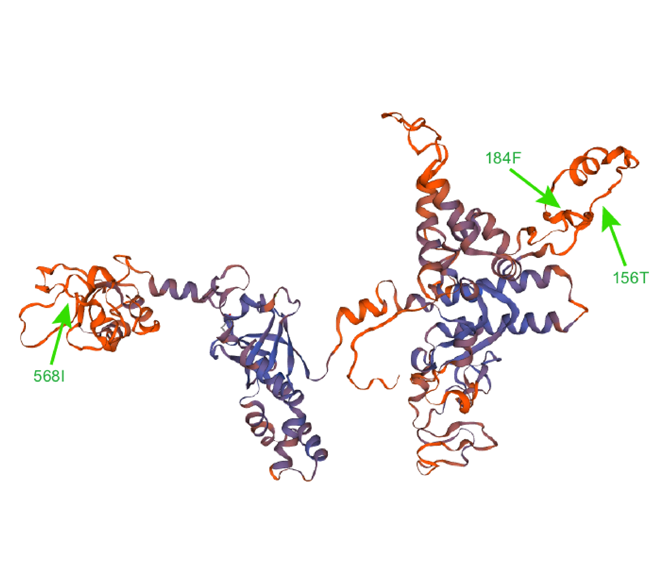

The rpoC1 gene encodes the RNA polymerase β' subunit protein, which binds to the DNA template during transcription, and the β-β' subunit complex formed with the β subunit constitutes a catalytic center for RNA synthesis. In this study, the rpoC1 gene mutations in ferns were surveyed. With Bayes factor greater than 20, HyPhy site model detected 3 positive selection sites and 541 negative selection sites; the PAML site model detected 10 positive selection sites, three of which had posterior probabilities greater than 99%. In addition, a phylogenetic tree of 64 ferns was constructed based on the maximum likelihood method. We calculated the transition rate, transversion rate, transition rate/transversion rate, synonymous substitution rate, nonsynonymous substitution rate, and synonymous substitution rate/nonsynonymous substitution rate by HyPhy to analyze the relationship between intron loss of rpoC1 gene and molecular evolution rates. The results indicate that intron loss of the rpoC1 gene might play a role in its transition rate, transversion rate and nonsynonymous substitution rate in ferns.

Key words: rpoC1; intron; positive selection site; selection pressure

Yang Peng , Yingjuan Su , Ting Wang . Intron Loss and Molecular Evolution Rate of rpoC1 in Ferns[J]. Chinese Bulletin of Botany, 2020 , 55(3) : 287 -298 . DOI: 10.11983/CBB19105

| [1] | 中国科学院中国植物志编辑委员会 (1959). 中国植物志, Vol.2. 北京: 科学出版社. pp. 106. |

| [2] | Akaike H (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Autom Control 19, 716-723. |

| [3] | Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D (2012). jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods 9, 772. |

| [4] | Downie SR, Katz-Downie DS, Rogers EJ, Zujewski HL, Small E (1998). Multiple independent losses of the plastid rpoC1 intron in Medicago (Fabaceae) as inferred from phylogenetic analyses of nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer sequences. Can J Bot 76, 791-803. |

| [5] | Downie SR, Llanas E, Katz-Downie DS (1996). Multiple independent losses of the rpoC1 intron in angiosperm chloroplast DNA’s. Syst Bot 21, 135-151. |

| [6] | Dubuisson JY (1997). rbcL sequences: a promising tool for the molecular systematics of the fern genus Trichomanes (Hymenophyllaceae)? Mol Phylogenet Evol 8, 128-138. |

| [7] | Gao L, Wang B, Wang ZW, Zhou Y, Su YJ, Wang T (2013). Plastome sequences of Lygodium japonicum and Marsilea crenata reveal the genome organization transformation from basal ferns to core Leptosporangiates. Genome Biol Evol 5, 1403-1407. |

| [8] | Guillon JM (2004). Phylogeny of Horsetails (Equisetum) based on the chloroplast rps4 gene and adjacent noncoding sequences. Syst Bot 29, 251-259. |

| [9] | Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O (2010). New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol 59, 307-321. |

| [10] | Hall TA (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/ 98/NT. Nucl Acid Symp Ser 41, 95-98. |

| [11] | Hansen AK, Gilbert LE, Simpson BB, Downie SR, Cervi AC, Jansen RK (2006). Phylogenetic relationships and chromosome number evolution in Passiflora. Syst Bot 31, 138-150. |

| [12] | He L, Qian J, Li XW, Sun ZY, Xu XL, Chen SL (2017). Complete chloroplast genome of medicinal plant Lonicera japonica: genome rearrangement, intron gain and loss, and implications for phylogenetic studies. Molecules 22, 249. |

| [13] | Hong XW, Zhang YP, Chu YW, Gao HF, Jiang ZG, Xiong SD (2008). Complete sequence determination and phylogenetic analysis of FKN among seven higher primates including homonids and old world monkeys. Hereditas 30, 595-601. |

| [14] | Katayama H, Ogihara Y (1993). Structural alterations of the chloroplast genome found in grasses are not common in monocots. Curr Genet 23, 160-165. |

| [15] | Kim HT, Chung MG, Kim KJ (2014). Chloroplast genome evolution in early diverged leptosporangiate ferns. Mol Cells 37, 372-382. |

| [16] | Korall P, Conant DS, Schneider H, Ueda K, Nishida H, Pryer KM (2006). On the phylogenetic position of Cystodium: it’s not a tree fern—it’s a polypod! Am Fern J 96, 45-53. |

| [17] | Lovis JD (1978). Evolutionary patterns and processes in ferns. Adv Bot Res 4, 229-415. |

| [18] | Morgan JT, Fink GR, Bartel DP (2019). Excised linear introns regulate growth in yeast. Nature 565, 606-611. |

| [19] | Newcomb RD, Campbell PM, Ollis DL, Cheah E, Russell RJ, Oakshott JG (1997). A single amino acid substitution converts a carboxylesterase to an organophosphorus hydrolase and confers insecticide resistance on a blowfly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94, 7464-7468. |

| [20] | Nielsen R, Yang Z (1998). Likelihood models for detecting positively selected amino acid sites and applications to the HIV-1 envelope gene. Genetics 148, 929-936. |

| [21] | Parenteau J, Maignon L, Berthoumieux M, Catala M, Gagnon V, Abou Elela S (2019). Introns are mediators of cell response to starvation. Nature 565, 612-617. |

| [22] | Perutz MF (1983). Species adaptation in a protein molecule. Mol Biol Evol 1, 1-28. |

| [23] | Pond SLK, Frost SDW, Muse SV (2005). HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics 21, 676-679. |

| [24] | Rothwell GW (1987). Complex paleozoic filicales in the evolutionary radiation of ferns. Am J Bot 74, 458-461. |

| [25] | Schuettpelz E, Pryer KM (2007). Fern phylogeny inferred from 400 leptosporangiate species and three plastid genes. Taxon 56, 1037-1050. |

| [26] | Smith AR, Pryer KM, Schuettpelz E, Korall P, Schneider H, Wolf PG (2006). A classification for extant ferns. Taxon 55, 705-731. |

| [27] | Taylor TN, Taylor EL, Krings M (2009). Paleobotany: the Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants, 2nd edn. Amsterdam: Academic Press. pp. 1-1252. |

| [28] | The Pteridophyte Phylogeny Group (2016). A community-derived classification for extant lycophytes and ferns. J Syst Evol 54, 563-603. |

| [29] | Thiede J, Schmidt SA, Rudolph B (2007). Phylogenetic implication of the chloroplast rpoC1 intron loss in the Aizoaceae (Caryophyllales). Biochem Syst Ecol 35, 372-380. |

| [30] | Wallace RS, Cota JH (1996). An intron loss in the chloroplast gene rpoC1 supports a monophyletic origin for the subfamily Cactoideae of the Cactaceae. Curr Genet 29, 275-281. |

| [31] | Weng ML, Blazier JC, Govindu M, Jansen RK (2014). Reconstruction of the ancestral plastid genome in Geraniaceae reveals a correlation between genome rearrangements, repeats, and nucleotide substitution rates. Mol Biol Evol 31, 645-659. |

| [32] | Yang ZH (1997). PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. CABIOS 13, 555-556. |

| [33] | Yang ZH (1998). Likelihood ratio tests for detecting positive selection and application to primate lysozyme evolution. Mol Biol Evol 15, 568-573. |

| [34] | Yang ZH (2005). Bayes empirical Bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol Biol Evol 22, 1107-1118. |

| [35] | Yang ZH (2007). PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol 24, 1586-1591. |

| [36] | Yang ZH, Nielsen R (2002). Codon-substitution models for detecting molecular adaptation at individual sites along specific lineages. Mol Biol Evol 19, 908-917. |

| [37] | Yang ZH, Swanson WJ, Vacquier VD (2000). Maximum- likelihood analysis of molecular adaptation in abalone sperm lysin reveals variable selective pressures among lineages and sites. Mol Biol Evol 17, 1446-1455. |

| [38] | Zhang JZ, Nielsen R, Yang ZH (2005). Evaluation of an improved branch-site likelihood method for detecting positive selection at the molecular level. Mol Biol Evol 22, 2472-2479. |

| [39] | Zuckerkandl E, Pauling LE (1962). Molecular disease, evolution, and genic heterogeneity. In: Kasha M, Pullman B, eds. Horizons in Biochemistry. New York: Academic Press. pp. 189-225. |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |