表观遗传调控植物分枝/分蘖研究进展

收稿日期: 2022-02-10

修回日期: 2022-05-11

网络出版日期: 2022-05-11

基金资助

山东省重点研发计划(2021LZGC020);国家自然科学基金(31670279);国家自然科学基金(31271311)

Research Progresses on Epigenetic Regulation of Plant Branching/Tillering

Received date: 2022-02-10

Revised date: 2022-05-11

Online published: 2022-05-11

刘婷 , 王天浩 , 淳雁 , 李学勇 , 赵金凤 . 表观遗传调控植物分枝/分蘖研究进展[J]. 植物学报, 2022 , 57(4) : 532 -548 . DOI: 10.11983/CBB22027

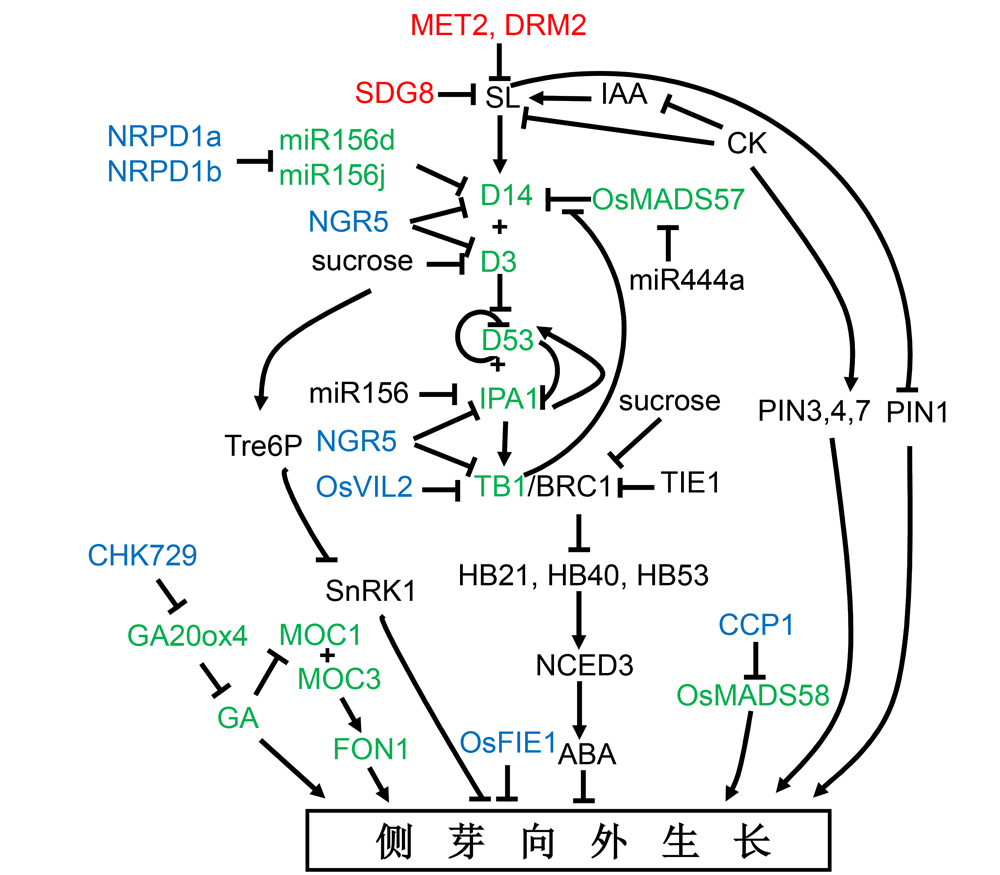

Tillers are one type of branches unique to graminaceous plants. Branch/tiller number is one of the key factors in determining crop yield. The number of branches/tillers is determined by both the number of axillary meristems formed in the leaf axils and the activity of lateral buds. Epigenetic modification regulates various processes of plant growth and development, but how epigenetic modifications regulate plant branch/tiller number has not been systematically reported. This review summarized the latest research progresses in epigenetic regulation of axillary meristem formation and lateral bud outgrowth, and proposed the future research fields of epigenetic regulation of plant branching/tillering, which will provide theoretical guidance for the breeding of improved crop varieties through epigenetic modifications.

| [1] | 南楠, 曾凡锁, 詹亚光 (2008). 植物DNA甲基化及其研究策略. 植物学通报 25, 102-111. |

| [2] | Aida M, Ishida T, Fukaki H, Fujisawa H, Tasaka M (1997). Genes involved in organ separation in Arabidopsis: an analysis of the cup-shaped cotyledon mutant. Plant Cell 9, 841-857. |

| [3] | Aida M, Ishida T, Tasaka M (1999). Shoot apical meristem and cotyledon formation during Arabidopsis embryogenesis: interaction among the CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON and SHOOT MERISTEMLESS genes. Development 126, 1563-1570. |

| [4] | Alam MM, Hammer GL, Van Oosterom EJ, Cruickshank AW, Hunt CH, Jordan DR (2014). A physiological framework to explain genetic and environmental regula-tion of tillering in sorghum. New Phytol 203, 155-167. |

| [5] | Al-Babili S, Bouwmeester HJ (2015). Strigolactones, a novel carotenoid-derived plant hormone. Annu Rev Plant Biol 66, 161-186. |

| [6] | Arite T, Iwata H, Ohshima K, Maekawa M, Nakajima M, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Kyozuka J (2007). DWARF10, an RMS1/MAX4/DAD1 ortholog, controls lateral bud outgrowth in rice. Plant J 51, 1019-1029. |

| [7] | Balla J, Kalousek P, Reinöhl V, Friml J, Procházka S (2011). Competitive canalization of PIN-dependent auxin flow from axillary buds controls pea bud outgrowth. Plant J 65, 571-577. |

| [8] | Balla J, Medveďová Z, Kalousek P, Matiješčuková N, Friml J, Reinöhl V, Procházka S (2016). Auxin flow- mediated competition between axillary buds to restore apical dominance. Sci Rep 6, 35955. |

| [9] | Barbier F, Péron T, Lecerf M, Perez-Garcia MD, Barrière Q, Rolčík J, Boutet-Mercey S, Citerne S, Lemoine R, Porcheron B, Roman H, Leduc N, Le Gourrierec J, Bertheloot J, Sakr S (2015). Sucrose is an early modulator of the key hormonal mechanisms controlling bud outgrowth in Rosa hybrida. J Exp Bot 66, 2569-2582. |

| [10] | Basile A, Fambrini M, Tani C, Shukla V, Licausi F, Pugliesi C (2019). The Ha-ROXL gene is required for initiation of axillary and floral meristems in sunflower. Genesis 57, e23307. |

| [11] | Bennett T, Hines G, Van Rongen M, Waldie T, Sawchuk MG, Scarpella E, Ljung K, Leyser O (2016). Connective auxin transport in the shoot facilitates communication between shoot apices. PLoS Biol 14, e1002446. |

| [12] | Berdasco M, Alcázar R, Garcia-Ortiz MV, Ballestar E, Fernández AF, Roldán-Arjona T, Tiburcio AF, Altabella T, Buisine N, Quesneville H, Baudry A, Lepiniec L, Alaminos M, Rodríguez R, Lloyd A, Colot V, Bender J, Canal MJ, Esteller M, Fraga MF (2008). Promoter DNA hypermethylation and gene repression in undifferentiated Arabidopsis cells. Arabidopsis 3, e3306. |

| [13] | Berger SL (2007). The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature 447, 407-412. |

| [14] | Beveridge CA, Symons GM, Murfet IC, Ross JJ, Rameau C (1997). The rms1 mutant of pea has elevated indole-3-acetic acid levels and reduced root-sap zeatin riboside content but increased branching controlled by graft-transmissible signal(s). Plant Physiol 115, 1251-1258. |

| [15] | Bian SM, Li J, Tian G, Cui YH, Hou YM, Qiu WD (2016). Combinatorial regulation of CLF and SDG8 during Arabidopsis shoot branching. Acta Physiol Plant 38, 173. |

| [16] | Braun N, De Saint Germain A, Pillot JP, Boutet-Mercey S, Dalmais M, Antoniadi I, Li X, Maia-Grondard A, Le Signor C, Bouteiller N, Luo D, Bendahmane A, Turnbull C, Rameau C (2012). The pea TCP transcription factor PsBRC1 acts downstream of strigolactones to control shoot branching. Plant Physiol 158, 225-238. |

| [17] | Brewer PB, Dun EA, Ferguson BJ, Rameau C, Beveridge CA (2009). Strigolactone acts downstream of auxin to regulate bud outgrowth in pea and Arabidopsis. Plant Phy- siol 150, 482-493. |

| [18] | Brewer PB, Dun EA, Gui RY, Mason MG, Beveridge CA (2015). Strigolactone inhibition of branching independent of polar auxin transport. Plant Physiol 168, 1820-1829. |

| [19] | Burnett AC, Rogers A, Rees M, Osborne CP (2016). Carbon source-sink limitations differ between two species with contrasting growth strategies. Plant Cell Environ 39, 2460-2472. |

| [20] | Cazzonelli CI, Cuttriss AJ, Cossetto SB, Pye W, Crisp P, Whelan J, Finnegan EJ, Turnbull C, Pogson BJ (2009). Regulation of carotenoid composition and shoot branching in Arabidopsis by a chromatin modifying histone methyltransferase, SDG8. Plant Cell 21, 39-53. |

| [21] | Chabikwa TG, Brewer PB, Beveridge CA (2019). Initial bud outgrowth occurs independent of auxin flow from out of buds. Plant Physiol 179, 55-65. |

| [22] | Chao WS, Doğramaci M, Horvath DP, Anderson JV, Foley ME (2016). Phytohormone balance and stress-rela- ted cellular responses are involved in the transition from bud to shoot growth in leafy spurge. BMC Plant Biol 16, 47. |

| [23] | Chen FY, Jiang LR, Zheng JS, Huang RY, Wang HC, Hong ZL, Huang YM (2014). Identification of differentially expressed proteins and phosphorylated proteins in rice seedlings in response to strigolactone treatment. PLoS One 9, e93947. |

| [24] | Chevalier F, Nieminen K, Sanchez-Ferrero JC, Rodriguez ML, Chagoyen M, Hardtke CS, Cubas P (2014). Strigolactone promotes degradation of DWARF14, an α/β hydrolase essential for strigolactone signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 1134-1150. |

| [25] | Crawford S, Shinohara N, Sieberer T, Williamson L, George G, Hepworth J, Müller D, Domagalska MA, Leyser O (2010). Strigolactones enhance competition bet- ween shoot branches by dampening auxin transport. Development 137, 2905-2913. |

| [26] | Dierck R, De Keyser E, De Riek J, Dhooghe E, Van Huylenbroeck J, Prinsen E, Van Der Straeten D (2016). Change in auxin and cytokinin levels coincides with al-tered expression of branching genes during axillary bud outgrowth in chrysanthemum. PLoS One 11, e0161732. |

| [27] | Doebley J, Stec A, Gustus C (1995). Teosinte branched1 and the origin of maize: evidence for epistasis and the evolution of dominance. Genetics 141, 333-346. |

| [28] | Domagalska MA, Leyser O (2011). Signal integration in the control of shoot branching. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12, 211-221. |

| [29] | Dun EA, Brewer PB, Beveridge CA (2009). Strigolactones: discovery of the elusive shoot branching hormone. Trends Plant Sci 14, 364-372. |

| [30] | Dun EA, De Saint Germain A, Rameau C, Beveridge CA (2012). Antagonistic action of strigolactone and cytokinin in bud outgrowth control. Plant Physiol 158, 487-498. |

| [31] | Endoh M, Endo TA, Endoh T, Isono KI, Sharif J, Ohara O, Toyoda T, Ito T, Eskeland R, Bickmore WA, Vidal M, Bernstein BE, Koseki H (2012). Histone H2A mono- ubiquitination is a crucial step to mediate PRC1-dependent repression of developmental genes to maintain ES cell identity. Plant Physiol 8, e1002774. |

| [32] | Eshed Y, Baum SF, Perea JV, Bowman JL (2001). Establishment of polarity in lateral organs of plants. Curr Biol 11, 1251-1260. |

| [33] | Fambrini M, Salvini M, Pugliesi C (2017). Molecular cloning, phylogenetic analysis, and expression patterns of LATERAL SUPPRESSOR-LIKE and REGULATOR OF AXILLARY MERISTEM FORMATION-LIKE genes in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Dev Genes Evol 227, 159-170. |

| [34] | Ferguson BJ, Beveridge CA (2009). Roles for auxin, cytokinin, and strigolactone in regulating shoot branching. Plant Physiol 149, 1929-1944. |

| [35] | Fichtner F, Barbier FF, Feil R, Watanabe M, Annunziata MG, Chabikwa TG, Höfgen R, Stitt M, Beveridge CA, Lunn JE (2017). Trehalose 6-phosphate is involved in triggering axillary bud outgrowth in garden pea (Pisum sativum L.). Plant J 92, 611-623. |

| [36] | Figueroa CM, Lunn JE (2016). A tale of two sugars: trehalose 6-phosphate and sucrose. Plant Physiol 172, 7-27. |

| [37] | Finlayson SA (2007). Arabidopsis TEOSINTE BRANCHED1- LIKE 1 regulates axillary bud outgrowth and is homologous to monocot TEOSINTE BRANCHED1. Plant Cell Physiol 48, 667-677. |

| [38] | Förderer A, Zhou Y, Turck F (2016). The age of multiplexity: recruitment and interactions of Polycomb complexes in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 29, 169-178. |

| [39] | Girault T, Abidi F, Sigogne M, Pelleschi-Travier S, Bou-maza R, Sakr S, Leduc N (2010). Sugars are under light control during bud burst in Rosa sp. Plant Cell Environ 33, 1339-1350. |

| [40] | Gomez-Roldan V, Fermas S, Brewer PB, Puech-Pagès V, Dun EA, Pillot JP, Letisse F, Matusova R, Danoun S, Portais JC, Bouwmeester H, Bécard G, Beveridge CA, Rameau C, Rochange SF (2008). Strigolactone inhibition of shoot branching. Nature 455, 189-194. |

| [41] | González-Grandío E, Pajoro A, Franco-Zorrilla JM, Tarancón C, Immink RGH, Cubas P (2017). Abscisic acid signaling is controlled by a BRANCHED1/HD-ZIP I cascade in Arabidopsis axillary buds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114, E245-E254. |

| [42] | González-Grandío E, Poza-Carrión C, Sorzano COS, Cubas P (2013). BRANCHED1 promotes axillary bud dormancy in response to shade in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 834-850. |

| [43] | Greb T, Clarenz O, Schäfer E, Müller D, Herrero R, Schmitz G, Theres K (2003). Molecular analysis of the LATERAL SUPPRESSOR gene in Arabidopsis reveals a conserved control mechanism for axillary meristem formation. Genes Dev 17, 1175-1187. |

| [44] | Griffiths CA, Paul MJ, Foyer CH (2016). Metabolite transport and associated sugar signaling systems underpinning source/sink interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1857, 1715-1725. |

| [45] | Guo DS, Zhang JZ, Wang XL, Han X, Wei BY, Wang JQ, Li BX, Yu H, Huang QP, Gu HY, Qu LJ, Qin GJ (2015). The WRKY transcription factor WRKY71/EXB1 controls shoot branching by transcriptionally regulating RAX genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 27, 3112-3127. |

| [46] | Hall SM, Hillman JR (1975). Correlative inhibition of lateral bud growth in Phaseolus vulgaris L. timing of bud growth following decapitation. Planta 123, 137-143. |

| [47] | Hibara KI, Karim MR, Takada S, Taoka KI, Furutani M, Aida M, Tasaka M (2006). Arabidopsis CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON3 regulates postembryonic shoot meristem and organ boundary formation. Plant Cell 18, 2946-2957. |

| [48] | Hubbard L, McSteen P, Doebley J, Hake S (2002). Expression patterns and mutant phenotype of teosinte branched1 correlate with growth suppression in maize and teo- sinte. Genetics 162, 1927-1935. |

| [49] | Ikeda Y, Banno H, Niu QW, Howell SH, Chua NH (2006). The ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION 2 gene in Arabidopsis regulates CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON 1 at the transcriptional level and controls cotyledon develop-ment. Plant Cell Physiol 47, 1443-1456. |

| [50] | Jiang L, Liu X, Xiong GS, Liu HH, Chen FL, Wang L, Meng XB, Liu GF, Yu H, Yuan YD, Yi W, Zhao LH, Ma HL, He YZ, Wu ZS, Melcher K, Qian Q, Xu HE, Wang YH, Li JY (2013). DWARF 53 acts as a repressor of strigolactone signaling in rice. Nature 504, 401-405. |

| [51] | Jiao YQ, Wang YH, Xue DW, Wang J, Yan MX, Liu GF, Dong GJ, Zeng DL, Lu ZF, Zhu XD, Qian Q, Li JY (2010). Regulation of OsSPL14 by OsmiR156 defines ideal plant architecture in rice. Nat Genet 42, 541-544. |

| [52] | Kebrom TH, Mullet JE (2015). Photosynthetic leaf area modulates tiller bud outgrowth in sorghum. Plant Cell Environ 38, 1471-1478. |

| [53] | Kebrom TH, Mullet JE (2016). Transcriptome profiling of tiller buds provides new insights into phyB regulation of tillering and indeterminate growth in Sorghum. Plant Physiol 170, 2232-2250. |

| [54] | Komatsu K, Maekawa M, Ujiie S, Satake Y, Furutani I, Okamoto H, Shimamoto K, Kyozuka J (2003). LAX and SPA: major regulators of shoot branching in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 11765-11770. |

| [55] | Kooistra SM, Helin K (2012). Molecular mechanisms and potential functions of histone demethylases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13, 297-311. |

| [56] | Lastdrager J, Hanson J, Smeekens S (2014). Sugar signals and the control of plant growth and development. J Exp Bot 65, 799-807. |

| [57] | Lemoine R, La Camera S, Atanassova R, Dédaldéchamp F, Allario T, Pourtau N, Bonnemain JL, Laloi M, Coutos-Thévenot P, Maurousset L, Faucher M, Girousse C, Lemonnier P, Parrilla J, Durand M (2013). Source-to- sink transport of sugar and regulation by environmental factors. Front Plant Sci 4, 272. |

| [58] | Li GL, Xu BX, Zhang YP, Xu YW, Khan NU, Xie JY, Sun XM, Guo HF, Wu ZY, Wang XQ, Zhang HL, Li JJ, Xu JL, Wang WS, Zhang ZY, Li ZC (2022). RGN1 controls grain number and shapes panicle architecture in rice. Plant Bio- technol J 20, 158-167. |

| [59] | Li L, Sheen J (2016). Dynamic and diverse sugar signaling. Curr Opin Plant Biol 33, 116-125 |

| [60] | Li XY, Qian Q, Fu ZM, Wang YH, Xiong GS, Zeng DL, Wang XQ, Liu XF, Teng S, Hiroshi F, Yuan M, Luo D, Han B, Li JY (2003). Control of tillering in rice. Nature 422, 618-621. |

| [61] | Liang YY, Ward S, Li P, Bennett T, Leyser O (2016). SMAX1-LIKE7 signals from the nucleus to regulate shoot development in Arabidopsis via partially EAR motif-independent mechanisms. Plant Cell 28, 1581-1601. |

| [62] | Liao ZG, Yu H, Duan JB, Yuan K, Yu CJ, Meng XB, Kou LQ, Chen MJ, Jing YH, Liu GF, Smith SM, Li JY (2019). SLR1 inhibits MOC1 degradation to coordinate tiller number and plant height in rice. Nat Commun 10, 2738. |

| [63] | Ligerot Y, De Saint Germain A, Waldie T, Troadec C, Citerne S, Kadakia N, Pillot JP, Prigge M, Aubert G, Bendahmane A, Leyser O, Estelle M, Debellé F, Rameau C (2017). The pea branching RMS2 gene en-codes the PsAFB4/5 auxin receptor and is involved in an auxin-strigolactone regulation loop. PLoS Genet 13, e1007089. |

| [64] | Lin QB, Wang D, Dong H, Gu SH, Cheng ZJ, Gong J, Qin RZ, Jiang L, Li G, Wang JL, Wu FQ, Guo XP, Zhang X, Lei CL, Wang HY, Wan JM (2012). Rice APC/CTE controls tillering by mediating the degradation of MONOCULM 1. Nat Commun 3, 752. |

| [65] | Liu XG, Kim YJ, Müller R, Yumul RE, Liu CY, Pan YY, Cao XF, Goodrich J, Chen XM (2011). AGAMOUS terminates floral stem cell maintenance in Arabidopsis by directly repressing WUSCHEL through recruitment of polycomb group proteins. Plant Cell 23, 3654-3670. |

| [66] | Long JA, Moan EI, Medford JI, Barton MK (1996). A member of the KNOTTED class of homeodomain proteins encoded by the STM gene of Arabidopsis. Nature 379, 66-69. |

| [67] | Loreti E, Alpi A, Perata P (2000). Glucose and disaccharide-sensing mechanisms modulate the expression of α-amylase in barley embryos. Plant Physiol 123, 939-948. |

| [68] | Lu ZF, Shao GN, Xiong JS, Jiao YQ, Wang J, Liu GF, Meng XB, Liang Y, Xiong GS, Wang YH, Li JY (2015). MONOCULM 3, an ortholog of WUSCHEL in rice, is required for tiller bud formation. J Genet Genomics 42, 71-78. |

| [69] | Lu ZF, Yu H, Xiong GS, Wang J, Jiao YQ, Liu GF, Jing YH, Meng XB, Hu XM, Qian Q, Fu XD, Wang YH, Li JY (2013). Genome-wide binding analysis of the transcription activator IDEAL PLANT ARCHITECTURE1 reveals a com- plex network regulating rice plant architecture. Plant Cell 25, 3743-3759. |

| [70] | Ma XD, Ma J, Zhai HH, Xin PY, Chu JF, Qiao YL, Han LZ (2015). CHR729 is a CHD3 protein that controls seedling development in rice. PLoS One 10, e0138934. |

| [71] | Mallory AC, Reinhart BJ, Jones-Rhoades MW, Tang GL, Zamore PD, Barton MK, Bartel DP (2004). MicroRNA control of PHABULOSA in leaf development: importance of pairing to the microRNA 5' region. EMBO J 23, 3356-3364. |

| [72] | Margalha L, Valerio C, Baena-González E (2016). Plant snRK1 kinases:structure, regulation, and function. In: Cordero MD, Viollet B, eds. AMP-activated Protein Kinase. AMP-activated Protein Kinase. Cham: Springer. pp. 403-438. |

| [73] | Mason MG, Ross JJ, Babst BA, Wienclaw BN, Beveridge CA (2014). Sugar demand, not auxin, is the initial regulator of apical dominance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 6092-6097. |

| [74] | McConnell JR, Barton MK (1998). Leaf polarity and meristem formation in Arabidopsis. Development 125, 2935-2942. |

| [75] | McConnell JR, Emery J, Eshed Y, Bao N, Bowman J, Barton MK (2001). Role of PHABULOSA and PHAVOLUTA in determining radial patterning in shoots. Nature 411, 709-713. |

| [76] | Meng WJ, Cheng ZJ, Sang YL, Zhang MM, Rong XF, Wang ZW, Tang YY, Zhang XS (2017). Type-B ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATORs specify the shoot stem cell niche by dual regulation of WUSCHEL. Plant Cell 29, 1357-1372. |

| [77] | Minakuchi K, Kameoka H, Yasuno N, Umehara M, Luo L, Kobayashi K, Hanada A, Ueno K, Asami T, Yamaguchi S, Kyozuka J (2010). FINE CULM1 (FC1) works downstream of strigolactones to inhibit the outgrowth of axillary buds in rice. Plant Cell Physiol 51, 1127-1135. |

| [78] | Moreno-Pachon NM, Mutimawurugo MC, Heynen E, Sergeeva L, Benders A, Blilou I, Hilhorst HWM, Immink RGH (2018). Role of Tulipa gesneriana TEOSINTE BRANCHED1 (TgTB1) in the control of axillary bud outgrowth in bulbs. Plant Reprod 31, 145-157. |

| [79] | Mozgova I, Hennig L (2015). The polycomb group protein regulatory network. Annu Rev Plant Biol 66, 269-296. |

| [80] | Mu?ller D, Schmitz G, Theres K (2006). Blind homologous R2R3 Myb genes control the pattern of lateral meristem initiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 586-597. |

| [81] | Müller D, Waldie T, Miyawaki K, To JPC, Melnyk CW, Kieber JJ, Kakimoto T, Leyser O (2015). Cytokinin is required for escape but not release from auxin mediated apical dominance. Plant J 82, 874-886. |

| [82] | Ni J, Gao CC, Chen MS, Pan BZ, Ye KQ, Xu ZF (2015). Gibberellin promotes shoot branching in the perennial woody plant Jatropha curcas. Plant Cell Physiol 56, 1655-1666. |

| [83] | Otori K, Tamoi M, Tanabe N, Shigeoka S (2017). En-hancements in sucrose biosynthesis capacity affect shoot branching in Arabidopsis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 81, 1470-1477. |

| [84] | Otsuga D, DeGuzman B, Prigge MJ, Drews GN, Clark SE (2001). REVOLUTA regulates meristem initiation at lateral positions. Plant J 25, 223-236. |

| [85] | Patil SB, Barbier FF, Zhao JF, Zafar SA, Uzair M, Sun YL, Fang JJ, Perez-Garcia MD, Bertheloot J, Sakr S, Fichtner F, Chabikwa TG, Yuan SJ, Beveridge CA, Li XY (2022). Sucrose promotes D53 accumulation and tillering in rice. New Phytol 234, 122-136. |

| [86] | Patrick JW, Botha FC, Birch RG (2013). Metabolic engineering of sugars and simple sugar derivatives in plants. Plant Biotechnol J 11, 142-156. |

| [87] | Peng MS, Cui YH, Bi YM, Rothstein SJ (2006). AtMBD9: a protein with a methyl-CpG-binding domain regulates flowering time and shoot branching in Arabidopsis. Plant J 46, 282-296. |

| [88] | Phillips IDJ (1975) Apical dominance. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 26, 341-367. |

| [89] | Prigge MJ, Otsuga D, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Drews GN, Clark SE (2005). Class III homeodomain-leucine zipper gene family members have overlapping, antagonistic, and distinct roles in Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 17, 61-76. |

| [90] | Raman S, Greb T, Peaucelle A, Blein T, Laufs P, Theres K (2008). Interplay of miR164, CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON genes and LATERAL SUPPRESSOR controls axi- llary meristem formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 55, 65-76. |

| [91] | Rameau C, Bertheloot J, Leduc N, Andrieu B, Foucher F, Sakr S (2014). Multiple pathways regulate shoot branching. Front Plant Sci 5, 741. |

| [92] | Ringrose L, Paro R (2004). Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the polycomb and trithorax group proteins. Annu Rev Genet 38, 413-443. |

| [93] | Roman H, Girault T, Barbier F, Péron T, Brouard N, Pěnčik A, Novák O, Vian A, Sakr S, Lothier J, Le Gourrierec J, Leduc N (2016). Cytokinins are initial targets of light in the control of bud outgrowth. Plant Physiol 172, 489-509. |

| [94] | Saeed W, Naseem S, Ali Z (2017). Strigolactones biosynthesis and their role in abiotic stress resilience in plants: a critical review. Front Plant Sci 8, 1487. |

| [95] | Salam BB, Malka SK, Zhu XB, Gong HL, Ziv C, Te-per-Bamnolker P, Ori N, Jiang JM, Eshel D (2017). Etiolated stem branching is a result of systemic signaling associated with sucrose level. Plant Physiol 175, 734-745. |

| [96] | Schluepmann H, Pellny T, Van Dijken A, Smeekens S, Paul M (2003). Trehalose 6-phosphate is indispensable for carbohydrate utilization and growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 6849-6854. |

| [97] | Schmitz G, Tillmann E, Carriero F, Fiore C, Cellini F, Theres K (2002). The tomato Blind gene encodes a MYB transcription factor that controls the formation of lateral meristems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99, 1064-1069. |

| [98] | Schubert D, Primavesi L, Bishopp A, Roberts G, Doonan J, Jenuwein T, Goodrich J (2006). Silencing by plant polycomb-group genes requires dispersed trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27. EMBO J 25, 4638-4649. |

| [99] | Schumacher K, Schmitt T, Rossberg M, Schmitz G, Theres K (1999). The Lateral suppressor (Ls) gene of tomato encodes a new member of the VHIID protein fami- ly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96, 290-295. |

| [100] | Scofield S, Murison A, Jones A, Fozard J, Aida M, Band LR, Bennett M, Murray JAH (2018). Coordination of meristem and boundary functions by transcription factors in the SHOOT MERISTEMLESS regulatory network. Development 145, dev157081. |

| [101] | Seale M, Bennett T, Leyser O (2017). BRC1 expression regulates bud activation potential but is not necessary or sufficient for bud growth inhibition in Arabidopsis. Development 144, 1661-1673. |

| [102] | Seto Y, Yasui R, Kameoka H, Tamiru M, Cao MM, Terauchi R, Sakurada A, Hirano R, Kisugi T, Hanada A, Umehara M, Seo E, Akiyama K, Burke J, Takeda- Kamiya N, Li WQ, Hirano Y, Hakoshima T, Mashiguchi K, Noel JP, Kyozuka J, Yamaguchi S (2019). Strigolactone perception and deactivation by a hydrolase receptor DWARF14. Nat Commun 10, 191. |

| [103] | Shabek N, Ticchiarelli F, Mao HB, Hinds TR, Leyser O, Zheng N (2018). Structural plasticity of D3-D14 ubiquitin ligase in strigolactone signaling. Nature 563, 652-656. |

| [104] | Shao GN, Lu ZF, Xiong JS, Wang B, Jing YH, Meng XB, Liu GF, Ma HY, Liang Y, Chen F, Wang YH, Li JY, Yu H (2019). Tiller bud formation regulators MOC1 and MOC3 cooperatively promote tiller bud outgrowth by activating FON1 expression in rice. Mol Plant 12, 1090-1102. |

| [105] | Shi BH, Zhang C, Tian CH, Wang J, Wang Q, Xu TF, Xu Y, Ohno C, Sablowski R, Heisler MG, Theres K, Wang Y, Jiao YL (2016). Two-step regulation of a meristematic cell population acting in shoot branching in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 12, e1006168. |

| [106] | Shimizu-Sato S, Tanaka M, Mori H (2009). Auxin-cytokinin interactions in the control of shoot branching. Plant Mol Biol 69, 429-435. |

| [107] | Shinohara N, Taylor C, Leyser O (2013). Strigolactone can promote or inhibit shoot branching by triggering rapid depletion of the auxin efflux protein PIN1 from the plasma membrane. PLoS Biol 11, e1001474. |

| [108] | Song XG, Lu ZF, Yu H, Shao GN, Xiong JS, Meng XB, Jing YH, Liu GF, Xiong GS, Duan JB, Yao XF, Liu CM, Li HQ, Wang YH, Li JY (2017). IPA1 functions as a downstream transcription factor repressed by D53 in strigolactone signaling in rice. Cell Res 27, 1128-1141. |

| [109] | Soundappan I, Bennett T, Morffy N, Liang YY, Stanga JP, Abbas A, Leyser O, Nelson DC (2015). SMAX1- LIKE/D53 family members enable distinct MAX2-dependent responses to strigolactones and karrikins in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 27, 3143-3159. |

| [110] | Stirnberg P, Furner IJ, Leyser HMO (2007). MAX2 participates in an SCF complex which acts locally at the node to suppress shoot branching. Plant J 50, 80-94. |

| [111] | Tabuchi H, Zhang Y, Hattori S, Omae M, Shimizu-Sato S, Oikawa T, Qian Q, Nishimura M, Kitano H, Xie H, Fang XH, Yoshida H, Kyozuka J, Chen F, Sato Y (2011). LAX PANICLE2 of rice encodes a novel nuclear protein and regulates the formation of axillary meristems. Plant Cell 23, 3276-3287. |

| [112] | Takeda T, Suwa Y, Suzuki M, Kitano H, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Ashikari M, Matsuoka M, Ueguchi C (2003). The OsTB1 gene negatively regulates lateral branching in rice. Plant J 33, 513-520. |

| [113] | Talbert PB, Adler HT, Parks DW, Comai L (1995). The REVOLUTA gene is necessary for apical meristem development and for limiting cell divisions in the leaves and stems of Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 121, 2723-2735. |

| [114] | Tanaka W, Ohmori Y, Ushijima T, Matsusaka H, Matsushita T, Kumamaru T, Kawano S, Hirano HY (2015). Axillary meristem formation in rice requires the WUSCHEL ortholog TILLERS ABSENT1. Plant Cell 27, 1173-1184. |

| [115] | Tarancón C, González-Grandío E, Oliveros JC, Nicolas M, Cubas P (2017). A conserved carbon starvation response underlies bud dormancy in woody and herbaceous species. Front Plant Sci 8, 788. |

| [116] | Teichmann T, Muhr M (2015). Shaping plant architecture. Front Plant Sci 6, 233. |

| [117] | Tian CH, Zhang XN, He J, Yu HP, Wang Y, Shi BH, Han YY, Wang GX, Feng XM, Zhang C, Wang J, Qi JY, Yu R, Jiao YL (2014). An organ boundary-enriched gene regu-latory network uncovers regulatory hierarchies underlying axillary meristem initiation. Mol Syst Biol 10, 755. |

| [118] | Tsuda K, Ito Y, Sato Y, Kurata N (2011). Positive auto-regulation of a KNOX gene is essential for shoot apical meristem maintenance in rice. Plant Cell 23, 4368-4381. |

| [119] | Umehara M, Hanada A, Yoshida S, Akiyama K, Arite T, Takeda-Kamiya N, Magome H, Kamiya Y, Shirasu K, Yoneyama K, Kyozuka J, Yamaguchi S (2008). Inhibi-tion of shoot branching by new terpenoid plant hormones. Nature 455, 195-200. |

| [120] | Van Es SW, Muñoz-Gasca A, Romero-Campero FJ, González-Grandío E, De Los Reyes P, Tarancón C, Van Dijk ADJ, Van Esse W, Angenent GC, Immink R, Cubas P (2020). A gene regulatory network critical for axillary bud dormancy directly controlled by Arabidopsis BRANCHED1. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/2020.12.14.394403. |

| [121] | Van Rongen M, Bennett T, Ticchiarelli F, Leyser O (2019). Connective auxin transport contributes to strigo-lactone-mediated shoot branching control independent of the transcription factor BRC1. PLoS Genet 15, e1008023. |

| [122] | Vollbrecht E, Reiser L, Hake S (2000). Shoot meristem size is dependent on inbred background and presence of the maize homeobox gene, knotted1. Development 15, 3161-3172. |

| [123] | Waldie T, Leyser O (2018). Cytokinin targets auxin transport to promote shoot branching. Plant Physiol 177, 803-818. |

| [124] | Wang J, Tian CH, Zhang C, Shi BH, Cao XW, Zhang TQ, Zhao Z, Wang JW, Jiao YL (2017). Cytokinin signaling activates WUSCHEL expression during axillary meristem initiation. Plant Cell 29, 1373-1387. |

| [125] | Wang L, Wang B, Jiang L, Liu X, Li XL, Lu ZF, Meng XB, Wang YH, Smith SM, Li JY (2015). Strigolactone sig- naling in Arabidopsis regulates shoot development by targeting D53-like SMXL repressor proteins for ubiquiti-nation and degradation. Plant Cell 27, 3128-3142. |

| [126] | Wang L, Wang B, Yu H, Guo HY, Lin T, Kou LQ, Wang AQ, Shao N, Ma HY, Xiong GS, Li XQ, Yang J, Chu JF, Li JY (2020). Transcriptional regulation of strigolactone signaling in Arabidopsis. Nature 583, 277-281. |

| [127] | Wang Q, Kohlen W, Rossmann S, Vernoux T, Theres K (2014a). Auxin depletion from the leaf axil conditions com- petence for axillary meristem formation in Arabidopsis and tomato. Plant Cell 26, 2068-2079. |

| [128] | Wang Y, Wang J, Shi BH, Yu T, Qi JY, Meyerowitz EM, Jiao YL (2014b). The stem cell niche in leaf axils is es-tablished by auxin and cytokinin in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 2055-2067. |

| [129] | Waters MT, Gutjahr C, Bennett T, Nelson DC (2017). Strigolactone signaling and evolution. Annu Rev Plant Biol 68, 291-322. |

| [130] | Williams L, Grigg SP, Xie MT, Christensen S, Fletcher JC (2005). Regulation of Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem and lateral organ formation by microRNA miR166g and its AtHD-ZIP target genes. Development 132, 3657-3668. |

| [131] | Wu K, Wang SS, Song WZ, Zhang JQ, Wang Y, Liu Q, Yu JP, Ye YF, Li S, Chen JF, Zhao Y, Wang J, Wu XK, Wang MY, Zhang YJ, Liu BM, Wu YJ, Harberd NP, Fu XD (2020). Enhanced sustainable green revolution yield via nitrogen-responsive chromatin modulation in rice. Science 367, eaaz2046. |

| [132] | Wu LG, Birch RG (2011). Isomaltulose is actively metabo-lized in plant cells. Plant Physiol 157, 2094-2101. |

| [133] | Xin W, Wang ZC, Liang Y, Wang YH, Hu YX (2017). Dynamic expression reveals a two-step patterning of WUS and CLV3 during axillary shoot meristem formation in Arabidopsis. J Plant Physiol 214, 1-6. |

| [134] | Xu C, Wang YH, Yu YC, Duan JB, Liao ZF, Xiong GS, Meng XB, Liu GF, Qian Q, Li JY (2012). Degradation of MONOCULM 1 by APC/CTAD1 regulates rice tillering. Nat Commun 3, 750. |

| [135] | Xu L, Yuan K, Yuan M, Meng XB, Chen M, Wu JG, Li JY, Qi YJ (2020). Regulation of rice tillering by RNA-directed DNA methylation at miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements. Mol Plant 13, 851-863. |

| [136] | Yan DW, Zhang XM, Zhang L, Ye SH, Zeng LJ, Liu JY, Li Q, He ZH (2015). CURVED CHIMERIC PALEA 1 encoding an EMF1-like protein maintains epigenetic repression of OsMADS58 in rice palea development. Plant J 82, 12-24. |

| [137] | Yang F, Wang Q, Schmitz G, Müller D, Theres K (2012). The bHLH protein ROX acts in concert with RAX1 and LAS to modulate axillary meristem formation in Arabidop-sis. Plant J 71, 61-70. |

| [138] | Yang Y, Nicolas M, Zhang JZ, Yu H, Guo DS, Yuan RR, Zhang TT, Yang JZ, Cubas P, Qin GJ (2018). The TIE1 transcriptional repressor controls shoot branching by di-rectly repressing BRANCHED1 in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 14, e1007296. |

| [139] | Yao H, Skirpan A, Wardell B, Matthes MS, Best NB, McCubbin T, Durbak A, Smith T, Malcomber S, McSteen P (2019). The barren stalk2 gene is required for axi- llary meristem development in maize. Mol Plant 12, 374-389. |

| [140] | Yao RF, Ming ZH, Yan LM, Li SH, Wang F, Ma S, Yu CT, Yang M, Chen L, Chen LH, Li YW, Yan C, Miao D, Sun ZY, Yan JB, Sun YN, Wang L, Chu JF, Fan SL, He W, Deng HT, Nan FJ, Li JY, Rao ZH, Lou ZY, Xie DX (2016). DWARF14 is a non-canonical hormone receptor for strigolactone. Nature 536, 469-473. |

| [141] | Yoon J, Cho LH, Lee S, Pasriga R, Tun W, Yang J, Yoon H, Jeong HJ, Jeon JS, An G (2019). Chromatin interacting factor OsVIL2 is required for outgrowth of axillary buds in rice. Mol Cells 42, 858-868. |

| [142] | Young NF, Ferguson BJ, Antoniadi I, Bennett MH, Beveridge CA, Turnbull CGN (2014). Conditional auxin response and differential cytokinin profiles in shoot branching mutants. Plant Physiol 165, 1723-1736. |

| [143] | Zhang L, Yu H, Ma B, Liu GF, Wang JJ, Wang JM, Gao RC, Li JJ, Liu JY, Xu J, Zhang YY, Li Q, Huang XH, Xu JL, Li JM, Qian Q, Han B, He ZH, Li JY (2017a). A natural tandem array alleviates epigenetic repression of IPA1 and leads to superior yielding rice. Nat Commun 8, 14789. |

| [144] | Zhang LG, Cheng ZJ, Qin RZ, Qiu Y, Wang JL, Cui XK, Gu LF, Zhang X, Guo XP, Wang D, Jiang L, Wu CY, Wang HY, Cao XF, Wan JM (2012). Identification and characterization of an epiallele of FIE1 reveals a regulatory linkage between two epigenetic marks in rice. Plant Cell 24, 4407-4421. |

| [145] | Zhang QQ, Wang JG, Wang LY, Wang JF, Wang Q, Yu P, Bai MY, Fan M (2020). Gibberellin repression of axillary bud formation in Arabidopsis by modulation of DELLA- SPL9 complex activity. J Integr Plant Biol 62, 421-432. |

| [146] | Zhang TQ, Lian H, Zhou CM, Xu L, Jiao YL, Wang JW (2017b). A two-step model for de novo activation of WUSCHEL during plant shoot regeneration. Plant Cell 29, 1073-1087. |

| [147] | Zhao JF, Wang T, Wang MX, Liu YY, Yuan SJ, Gao YN, Yin L, Sun W, Peng LX, Zhang WH, Wan JM, Li XY (2014). DWARF3 participates in an SCF complex and associates with DWARF14 to suppress rice shoot branching. Plant Cell Physiol 55, 1096-1109. |

| [148] | Zhou F, Lin QB, Zhu LH, Ren YL, Zhou KN, Shabek N, Wu FQ, Mao HB, Dong W, Gan L, Ma WW, Gao H, Chen J, Yang C, Wang D, Tan JJ, Zhang X, Guo XP, Wang JL, Jiang L, Liu X, Chen WQ, Chu JF, Yan CY, Ueno K, Ito S, Asami T, Cheng ZJ, Wang J, Lei CL, Zhai HQ, Wu CY, Wang HY, Zheng N, Wan JM (2013). D14-SCFD3- dependent degradation of D53 regulates strigolactone sig- naling. Nature 504, 406-410. |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |